Aerial threat: why drone hacking could be bad news for the military

Unmanned aerial vehicles, more commonly called drones, are now a fundamental part of defence force capability, from intelligence gathering to unmanned engagement in military operations. But what happens if our own technology is turned against us?

Between 2015 and 2022, the global commercial drone market is expected to grow from A$5.95 billion to A$7.47 billion.

Drones are now being used in a host of applications, including agriculture, media, parcel delivery, and defence.

However, as with all IT technology, manufacturers and users may leave the digital doors unlocked. This potentially leaves opportunities for cyber-criminals and perhaps even cyber-warfare.

Imagine a defence operation in which a drone is sent out to spy on enemy territory. The enemy identifies the drone but instead of disabling it, compromises the sensors (vision, sonar, and so on) to inject false data. Acting upon such data could then result in inappropriate tactics and, in a worst case scenario, may even lead to avoidable casualties.

UK cybersecurity consultant James Dale warned earlier this year that “equipment is now available to hack drones so they can bypass technology controls”.

Drones are relatively cheap technologies for military use—certainly cheaper than the use of satellites for surveillance. Off-the-shelf drones can be used to gather intelligence, without any significant development effort.

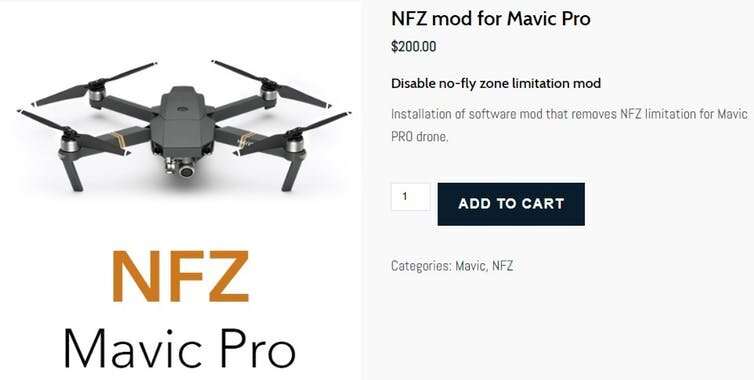

Meanwhile, governments have cracked down on illegal civilian drone use, and imposed no-fly zones around secure infrastructure such as airports. Drone manufacturers have been forced to provide “geofencing” software to avoid situations such as the recent drone strike in a Saudi oil field. However, cyber criminals are smart enough to bypass such controls and openly provide services to help consumers get past government and military-enforced no-fly zones.

Russian software company Coptersafe sells such modifications for a few hundred dollars. Anyone can buy a drone from a retail store, purchase the modifications, and then send their drone into no-fly zones such as military bases and airports. Ironically, Russia’s military base in Syria came under attack from drones last year.

Australia on the frontline

Australia is at the frontier of the military drone revolution, equipping itself with a fleet of hundreds of new drones. Lieutenant Colonel Keirin Joyce, discussing the program in a recent defence podcast, declared Australia will soon be “the most unmanned [air vehicle] army in the world per capita”.

It will be essential to safeguard every single component of this sophisticated unmanned aerial fleet from cyber attack.

When drones were developed, cyber security was not a priority. Let’s explore a few potential threats to drone technology:

drone navigation is based on the Global Positioning System (GPS). It’s possible an attacker can break the encryption of this communication channel. Fake signals can be fed to the targeted drone and the drone effectively gets lost. This type of attack can be launched without being in close physical proximitywith knowledge of the flight controller systems, hackers can gain access using “brute force” attacks. Then, the captured video footage can be manipulated to mislead the operator and influence ground operationsa drone fitted with sensors could be manipulated by injecting rogue signals. For example, the gyroscopes on a drone can be misled using an external source of audio energy. Cyber criminals may take advantage of this design characteristic to create false sensor readingsdrones’ onboard control systems are effectively small computers. Drone control systems (onboard and ground-based controllers) are also vulnerable to malicious software or Maldrone (malware for drones). The founder and CTO of CloudSEK, Rahul Sasi discovered a backdoor in the Parrot AR.Drone. Using malicious software, an attacker can establish remote communication and can take control of the drone. Attackers can also inject false data to mislead the operators. This type of malware can be installed silently without any visible sign to the operators. The consequences are significant if the drones are used for military operations.

As with traditional cyber-crime, it’s likely 2019 will see a sharp rise in drone-related incidents. However, these security breaches should not discourage the use of drones for personal, industrial or military applications. Drones are great tools in the era of smart cities, for instance.

But we should not forget the potential for cyber crime—and nowhere are the stakes higher than in military drone use. Clearly, the use of drones needs to be carefully regulated. And the first step is for the government and the Australian Defence Force to be fully aware of the risks.